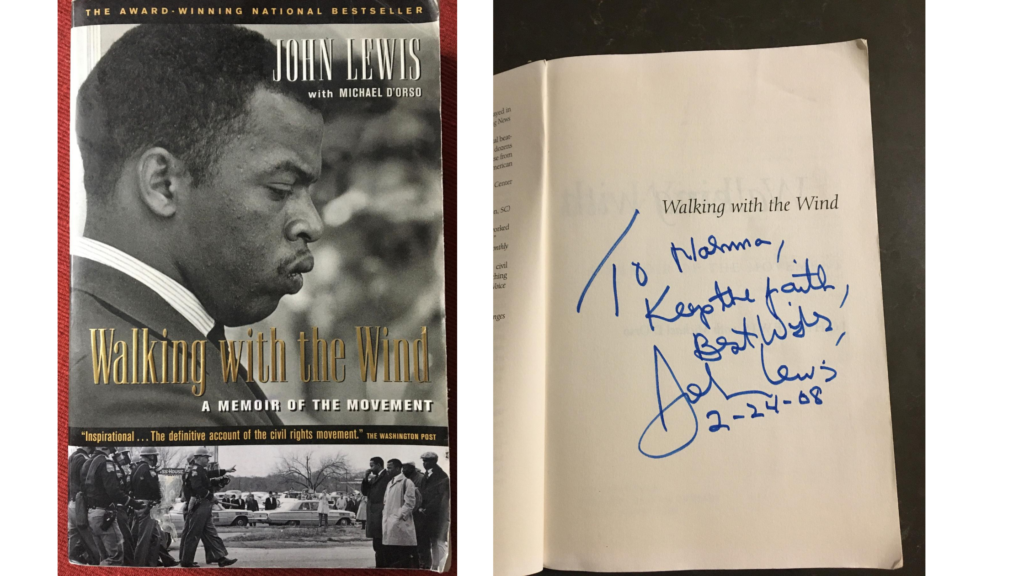

My autographed copy of John Lewis’ memoir

This week, a message from Deputy Director Nahma Nadich:

Though I knew that Congressman John Lewis was suffering from pancreatic cancer, I still reacted to the news of his death with surprised tears. Given all that he had endured through his blessedly long life and the countless times he subjected himself to state sanctioned violence in pursuit of equality for his people, I thought of him as invincible and perhaps, even, superhuman. As one of the few Civil Rights leaders granted the gift of longevity, his legacy was that much richer, filled with decades of insights and lessons about public leadership, not only as a young activist, but also as a member of Congress for over three decades. The moving and beautiful tributes we’ve watched and read this week have provided many invaluable lessons from the Congressman’s life about strategic and effective organizing for systemic change.

But the question that’s been confounding me this week is: how did this young firebrand, impatient to see change that was unconscionably overdue, mature into a public leader with such unflagging energy and determination? How did Lewis, who experienced not only the joy of seeing the first Black president elected, but also the horrifying backlash that followed, sustain his will to keep fighting and making “good trouble”? How was he able to witness the pernicious endurance of white supremacy and the continued dehumanization of Black people and the violence threatening their bodies, without losing his faith in the promise of America one day being realized?

As I’ve listened to Lewis’ wisdom in clips of interviews shared this week, I’m struck by the profound power of his commitment to nonviolence as a life-giving force and a source of moral clarity. His understanding of nonviolence wasn’t only as a strategic approach to movement building, but also as a guiding philosophy in relating to all human beings, including his opponents and even his enemies. This man, whose skull was fractured by state agents of white supremacy (none of whom has ever been held accountable for their brutality), cautioned us never to demean our enemies.

“To reconcile ourselves with one another, we must release our judgments and make peace with the fact that we are one. This country was founded on the ideal that we are all created equal. If we truly believe in the equality of all humankind, how can we put down and belittle one another? How can we disrespect and prejudge one another? How can we come to the point where we malign and hate one another?”

John Lewis, Across That Bridge: A Vision for Change and the Future of America

The words of this American hero ring so very true as I think about the degradation of our public discourse, and the speed with which we condemn those with whom we disagree. Rather than debate ideas and arguments on their merit, our default is to impugn motives and assassinate the character of those promoting the ideas. Throughout his life, Lewis was intent on building a “beloved community” (one that would not be “unkind”, “polarized” or “adversarial”), a core concept in the philosophy of nonviolence. What a profound vision to guide us at JCRC, as we seek to represent the organized Jewish community, a community with deeply shared values and commitments, co-existing with passionately held and often loudly diverse views across the ideological spectrum.

But the young activist, whose planned address at the March on Washington was toned down to avoid inflaming political leaders, also had a fire burning within him that was never extinguished. He understood that there was a time and place for battle. He advised, “Choose confrontation wisely, but when it is your time don’t be afraid to stand up, speak up, and speak out against injustice” in his book Across That Bridge: A Vision for Change and the Future of America.

One such time for him was at the 1995 Million Man March, which he chose not to join, eliciting much criticism at the time. In his own words,

“I did not march because I could not overlook the presence and central role of Louis Farrakhan, and so I refused to participate. I believe in freedom of speech but I also believe that we have an obligation to condemn speech that is racist, bigoted, anti-Semitic or hateful…The means by which we struggle must be consistent with the end we seek, and that includes the words we use to pursue those ends”.

John Lewis, Walking With the Wind

Among the many lessons this moral giant left us was this one; to refrain from gratuitous attacks against your opponents, but to discern those times when you must stand firm against clear expressions of hatred and bigotry, and that which must never be tolerated. And when you go to battle, do so with moral clarity and integrity.

The notion of relating charitably to our fellow human beings echoes the lesson we learn in Pirkei Avot (Ethics of the Fathers) to “…appoint yourself a teacher, and acquire yourself a companion, and judge all people with the scale weighted in their favor”. As we remember the remarkable legacy of John Lewis, the “Conscience of the Congress”, we give thanks for the gift of this teacher, heed his sage advice to treat each other kindly, and draw inspiration to build our own Beloved Community.

Shabbat Shalom,

Nahma