This blog post was originally published as an op-ed in The Forward.

At a Hanukkah party on Sunday night, Congresswoman-elect Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez shared that “generations and generations ago, my family consisted of Sephardic Jews.”

In doing so, she publicly joined a vast community of people, including my family, in embracing the space where Jewish and Latinx identities intersect.

It is a story that, sadly, has long sat at the margins of both the experiences.

My family story begins with a journey of exploration. In the early 1960s my mother, Diane Marie Sandoval, born and raised Mexican and Catholic in California, informed her parents that her path was leading her to conversion to Judaism.

My grandma was not enthused by her daughter’s decision, finding it difficult to reconcile it with her own faith and identity.

But my grandpa’s reaction was quite different. He told her, “I’ve always felt myself to be of Jewish soul and heritage.”

In the years that followed, my mother and others in our extended family embarked on a journey of discovery into our roots. This journey was made possible in large part by the meticulous record keeping of the Catholic Church in New Spain (Mexico, including the current U.S. southwest) and later by advances in DNA testing.

The record of my grandfather’s family takes us back to the earliest identifiable Sandoval of our line in Mexico, in the mid-18th century. While we have known ancestors named Pacheco, a historically Sephardic name, appearing in the records some 200 years ago, we eventually hit an adobe wall and were unable to trace them back farther.

In the end it is unprovable what Jewish ancestry nurtured Grandpa Joe’s Jewish “feels.”

The story takes a more remarkable and yet profoundly normal turn on my grandmother’s side.

Our Martinez family of New Mexico, again through church records, traces us directly back to Francisco Gomez Vicente. Born in 1576 in Portugal, he crossed the Atlantic and joined the Oñante’s Expedition. His was among the first families to settle Santa Fe, arriving in 1598.

His wife, Maria Ana Robledo Romero, came from a family known to be related to many Jews.

We know that the Gomez de Robledo family lived under suspicion of being hidden Jews. After his death, Francisco’s son, my great-uncle many times over, came under the eye of the Inquisition in New Spain. He was “examined” to determine whether he was a Jew and was found to be so, as my ancestor had circumcised his son.

After serving time in jail, my great-uncle appealed his case, and was examined once again — resulting, of course, in the same finding (one wonders how he hoped for another outcome).

This is just one story amongst thousands in the Spanish Jewish, or Sephardic, Diaspora. It is a story of how families made a difficult decision in the centuries after the expulsion of 1492 to conceal their identities and move to the edges of this new empire, just as Spain was expanding its reach.

These Sephardim were determined to put distance between themselves and the inquisitors. But they escaped as individuals, without rabbis and teachers.

There was only so much that could be passed on.

For my grandmother’s family, by the time that they fled in a harrowing 300 mile march from Santa Fe to El Paso de Norte after the Pueblo Uprising of 1680, they had lost any Jewish identity.

Three centuries years later, it was hard to reconcile a daughters’ choice with a mother’s strongly-held Catholic faith.

Other families held on with converso practices such as lighting candles in the basement every Friday night. But, as with my grandfather, an identity passed down only as lore can be very hard to prove.

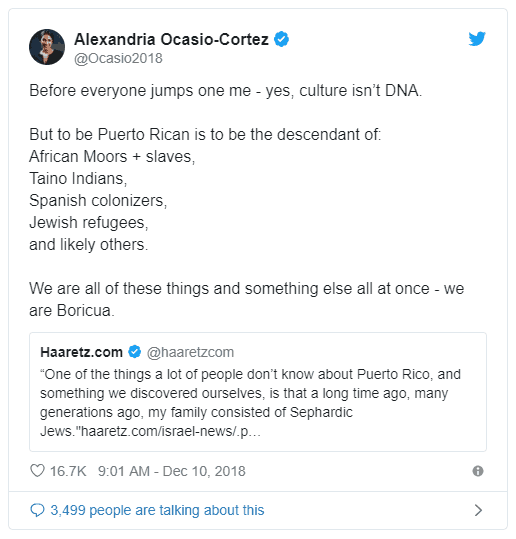

Ocasio-Cortez, in the course of her own personal journey through her history, made a profoundly normal discovery. As she tweeted:

“To be Puerto Rican is to be the descendant of: African Moors + slaves, Taino Indians, Spanish colonizers, Jewish refugees, and likely others.”

For myself, to be Mexican-American is to be the descendant of Spanish and French colonizers, of the Basque, of the Tarahumara native peoples and yes, of Jews.

There were Jews all over the place in New Spain.

What matters now, to paraphrase Professor Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi of Columbia University in his seminal work Zakhor (Memory), is not whether one can prove one’s ancestry through baptismal and Inquisition records or through DNA tests.

What matters is not whether one embraces an identity of being Jewish or practicing Judaism as faith.

What matters is whether this heritage of Jewish persecution, hiding, diaspora and identity is meaningful to you.

That this discovery is meaningful enough to Ocasio-Cortez that she chose to share it publicly should be celebrated by all of us.

Her story, and all of ours, are part of the Latinx story and equally part of the Jewish story.

By honoring her story, we honor our own heritage.